After a 2012 Rolling Stone editorial by noted environmentalist Bill McKibben calls for institutions to divest their holdings in fossil fuel companies, divestment movements have been sweeping college campuses across the country.

Following high-profile campaigns at Harvard, Stanford, and MIT, the Rollins Coalition for Sustainable Investment (RCSI) emerged this fall, calling for the Board of Trustees to divest the college’s endowment from the top 200 fossil fuel companies (as measured by energy reserves) and co-mingled funds.

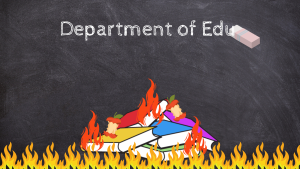

Though well-intentioned, RCSI’s calls for divestment are ultimately misguided.

Here are the three key reasons why I think that Rollins College ought not to divest:

1. The evidence indicates that divestment is unlikely to make a significant economic or political impact.

The 1980s anti-Apartheid movement—of which Rollins was a part—is often cited as a successful divestment campaign. Unfortunately, the evidence is not so clear.

A 1999 study conducted by economists at the University of Michigan and UCLA concludes that economic actions had little discernible effect in South Africa and that international condemnation, diplomatic, and social pressures were more likely responsible for ending apartheid.

Indeed, many of the most ardent divestment activists admit that its goals are not economic. The RCSI website states: “Divestment isn’t primarily an economic strategy, but a moral and political one.”

I agree. If the goals are to condemn and shame a particular industry in the hopes of weakening its political clout, it seems that these goals can be achieved without collective economic action. The example of South Africa proves that.

2. Manipulation of financial resources to make a political statement runs counter to the core academic mission of an educational institution.

RCSI points out the college’s stated commitment to “global citizenship” and “environmental stewardship” as reasons to divest.

I disagree. These values are best achieved when the institution makes decisions based on its academic imperatives. Rollins is fundamentally an academic institution with the responsibility to manage its funds in the way that best provides ongoing resources to its students, faculty, and alumni.

In an official statement from 2013, Harvard University President Drew Faust said it best in her rejection of fossil fuel divestment: “Conceiving of the endowment not as an economic resource, but as a tool to inject the University into the political process or as a lever to exert economic pressure for social purposes, can entail serious risks to the independence of the academic enterprise.”

Decisions on where to invest ought to be based primarily on fiscal prudence, not social and political objectives—however well-intentioned they may be. Agreeing to use the college’s endowment as a tool for promoting political change sets a dangerous precedent.

The college can and should use its influence to benefit society. The way it does that is through educating and empowering its students and faculty to pursue meaningful research, careers, and civic engagement, not manipulating its financial resources to make a moral statement.

3. Divestment campaigns rely on public shaming and exacerbation of political divisions—tactics unlikely to foster the broad consensus necessary to address climate change.

Frank Wolak, an economist and Stanford University’s Director of the Program on Energy and Sustainable Development, along with many of the world’s preeminent environmentalists, argues that the best method to address climate change is by establishing “a stable, predictable price on carbon.”

Political consensus and public goodwill toward combating climate change is necessary to achieve such a result. The divestment campaign, which relies on demonizing the fossil fuel industry and forcing individuals and institutions to take sides, is likely to further entrench partisan divides and make consensus less attainable.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology President L. Rafael Reif stated as much in the University’s 2015 Climate Plan of Action.

“Combatting climate change will require intense collaboration across the research community, industry, and government. Divestment would interfere with our ability to collaborate and to convene opposing groups to drive progress, at what may be a historic tipping point.”

A movement that engages fossil fuel producers as part of the solution, while recognizing the variety of options for dealing with climate change, though not as bold and immediately satisfying as a divestment pledge, is far more likely to achieve the worthy and necessary goal of halting climate change.

Be First to Comment