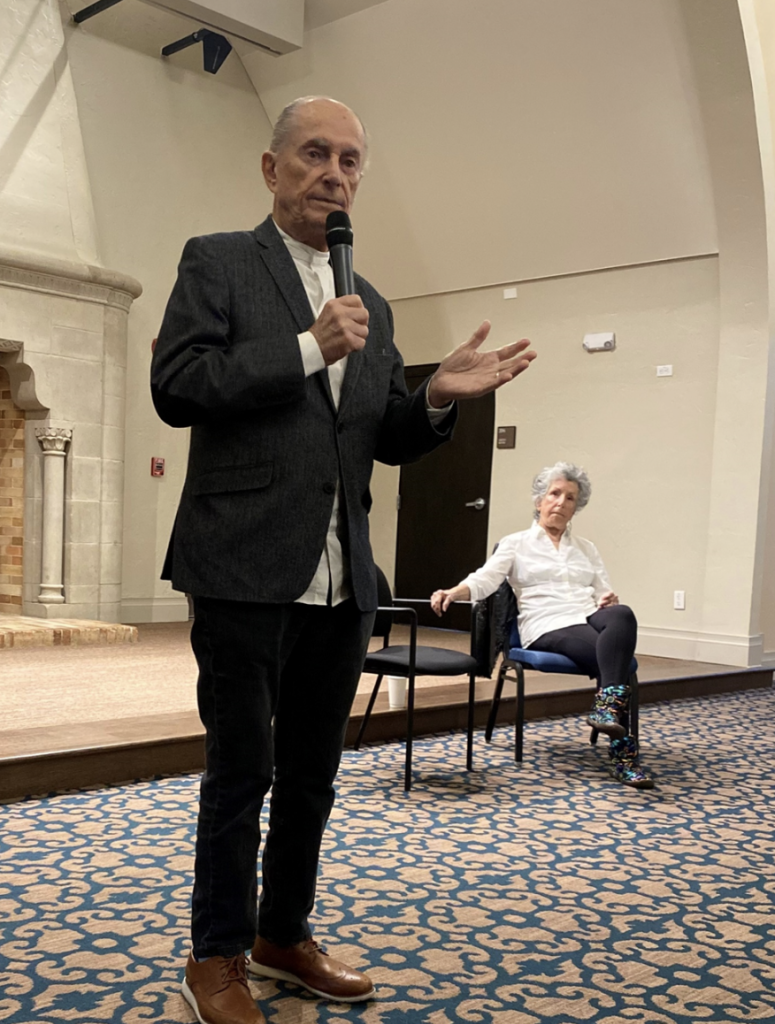

Allan J. Hall is a University of Florida law graduate and a retired professor. He came to Rollins from Miami Beach, FL. However, he was born on much more distant soil—in Krakow, Poland, just four years before the start of World War II. Now 88 years old, he was welcomed here by Rollins Hillel to tell students, faculty, and staff his story as a survivor of the Holocaust.

Entering the Pavilion, guests were met by a sense of warm reverence: as the audience congregated around the rows of chairs, they spoke to each other in hushed tones, though they didn’t hold back from the occasional laughter.

Moving among the crowd was Lori Gold, Hall’s wife—and coach, as he later introduced her. She invited those sitting at the back of the room to move closer to the front. “Allan wants to make eye contact, and to make sure everyone can hear each other,” she said.

Hall, too, introduced himself to several attendees before he and Gold made their way to the front of the room.

Hall’s talk began with a disclaimer: that the primary stories of the Holocaust could never be told. It was “a genocide within a genocide,” he said. Not only were 6 million Jewish people killed, but 5 million non-Jewish people. World War II resulted in the deaths of 60 to 80 million total Europeans, including soldiers and civilians on all fronts.

“After 50 to 60 years of looking at [the history], I know nothing,” Hall said. “Nobody, nobody can be an expert.” He encouraged the attendees to correct him if he presented any inaccuracies and to interrupt with questions.

Hall presented a series of “thumbnail sketches” from his life as a Jewish child in Poland from 1939 to 1944. What was perhaps most striking about his story was the succession of near misses, and the combination of strangers’ courageous generosity and sheer luck that prevented Hall and his family from being captured and killed by Nazi soldiers.

A detailed account of Hall’s life can be read in his memoir, Hiding in Plain Sight, which is available for free download rather than for purchase.

Concluding his talk, Hall once again encouraged the audience to ask questions. When met with applause, he remarked, “Now I’m confused. I didn’t ask for applause—I asked for questions and comments!”

One audience member asked Hall what gave him hope throughout the war.

“Hope is not a word we focused on,” he answered. However, he recalled how every day, his mother would tell him that they had won. According to Hall, “Every day we survived was a victory” against the Nazis who wanted them dead.

Another attendee asked whether it took Hall a long time to recover from the trauma he experienced before going public with his story.

Hall said that some had told him he was not a survivor because he had never been to a concentration camp, despite the years he had lost in hiding and the violence he had witnessed and endured. Well into adulthood, his brother eventually encouraged him to speak. Hall quoted him as saying, “‘The old survivors are dying; there is no one left to speak. It is an obligation.’”

When asked about the state of Holocaust education in the U.S., Hall said that it is important, but currently inadequate.

“We need to speak about and think about genocide in general […] and what responsibility we have to other human beings,” he said.

Gold had her own question for Hall: “How did you become the person you are today?”

Hall recalled moments of deep depression he experienced in his first semester at the University of Florida. He credited his fraternity brothers, who got him out of bed and to a counseling clinic, for putting him in his current position. He encouraged the audience to get out of bed and seek therapy if they ever feel down for more than a reasonable time.

Aside from mental health care, Hall stressed the importance of pursuing lifelong education. “You can lose anything,” he said, “but the one thing you never lose, ever, is your education.”

One of the most important takeaways Hall and Gold left the audience was to speak up against future atrocities.

“If you see wrongdoing,” Hall urged, “for God’s sake, don’t be passive about it. Do something about it. Scream about it. Complain.”

“When the Nazis came into power, there was only one group of students that resisted,” he added, referencing the White Rose movement. “They were wiped out, of course. But if something had been done much earlier, who knows what might not have happened.”

“I think the event tonight went very well,” said Heidi Zissman, associate director of Jewish Student Life at Rollins. “It was really nice to hear a firsthand story. There’s gonna be less and less opportunities, so I appreciate Allan Hall coming to Rollins College to share.”

Comments are closed.