Authors: Zoe Pearson, Heather Borochaner, & Olivia Llanio

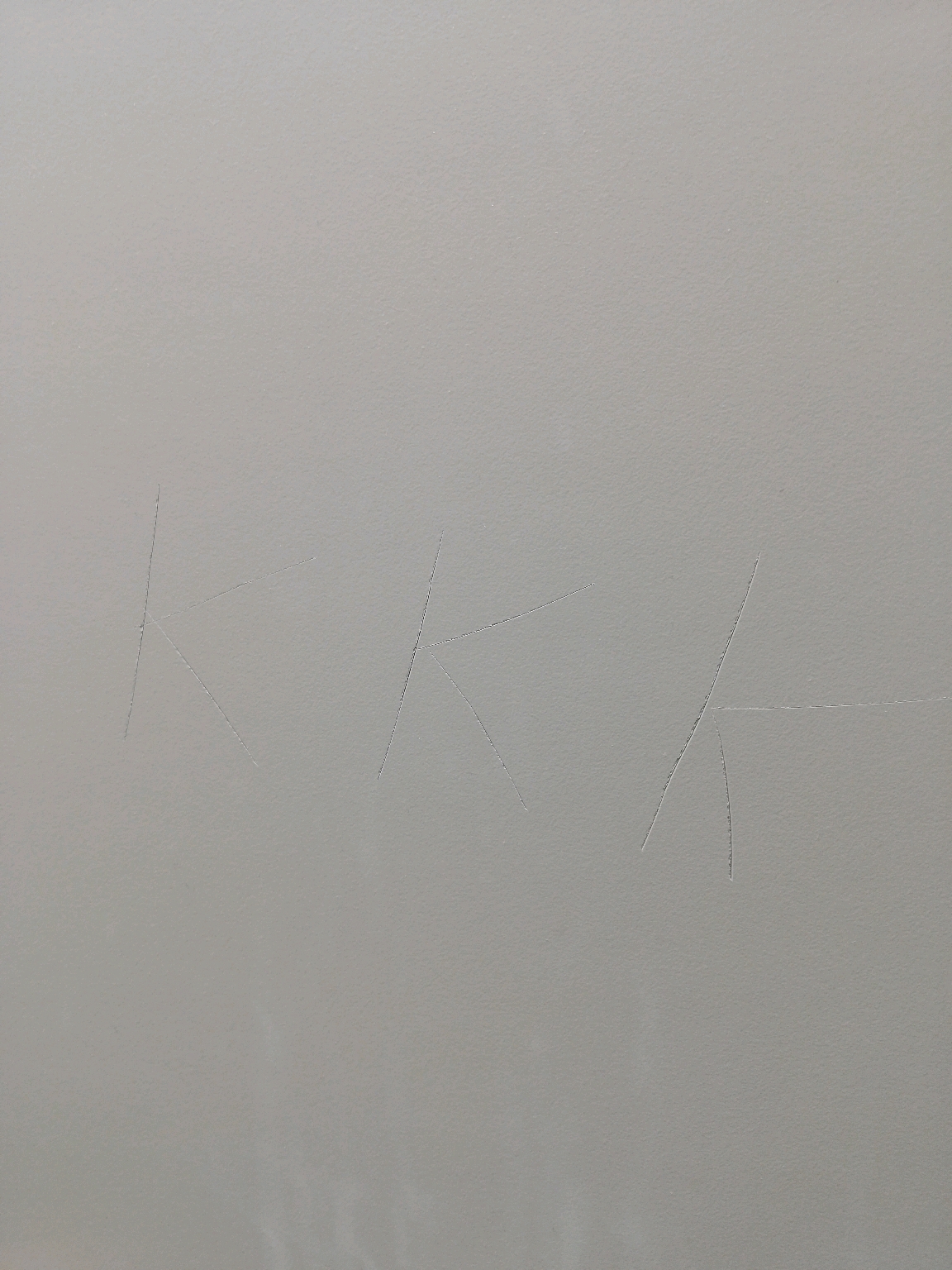

A student recently discovered the letters “KKK” carved into a Rollins bathroom stall, adding to the increasing number of discriminatory acts that have defaced campus property in the past three years.

The racist carving marks the third act of biased vandalism reported this spring and the sixth act in the past two years.

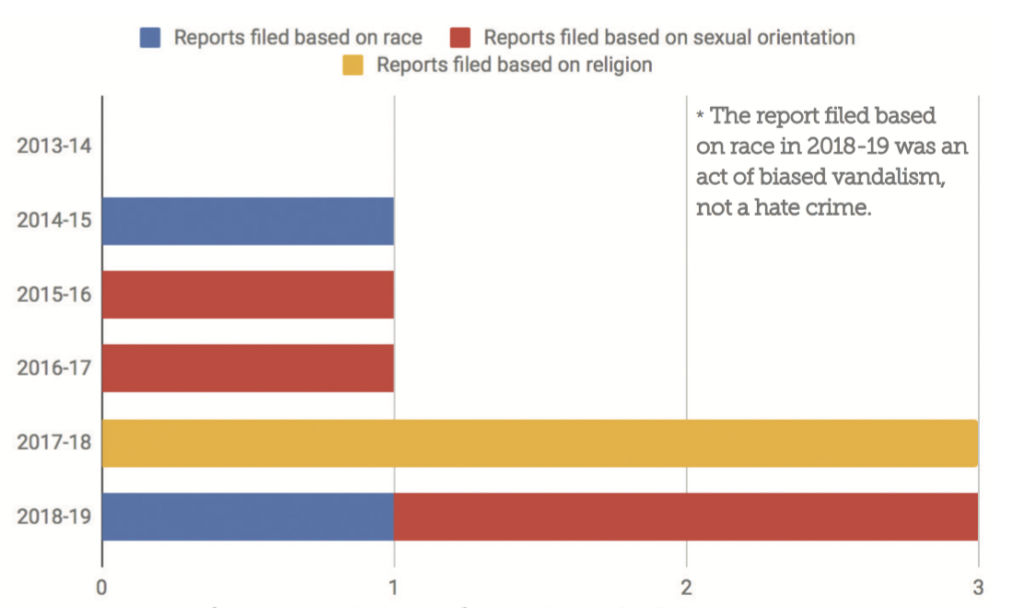

Since 2016, there has been a steady increase in hate crimes on campus. Spring and fall of 2016 saw only two hate crimes reported, and then spring 2017 saw three in just five weeks. A similar wave has struck campus again, as two hate crimes and one act of racist vandalism have been reported this semester.

The most recent “KKK” carving was discovered by a student on Tuesday, March 19 on a men’s bathroom stall in the Cornell Social Sciences Building, which houses offices and classrooms used by the departments of Communication, Education, Economics, and Critical Media and Cultural Studies.

The student returned to class and reported it to his professor, Dr. Matthew Nichter, who then took a photo of the stall and reported it to Campus Safety. Nichter assumed a campus-wide email would be sent out, as is what happens when instances of similar nature occur.

While the symbol represents an organization that historically targets minority groups, specifically black and Jewish people, Campus Safety deemed that the act was not a hate crime because in this specific instance, the letters were not targeting a specific individual or group.

Ken Miller, assistant vice president of Public Safety, evaluated the incident with several others and a consultant who he chose not to name, and they collectively decided it was an act of vandalism, which does not require a Timely Notification email to be sent to the College.

Miller said that when he evaluates hate crimes, he has to determine the perpetrator’s intention. “In this particular case, it wasn’t directed at any one particular person so we couldn’t determine that [intent],” said Miller. “As such, it was labeled as a vandalism case, not as a hate crime.”

According to the Clery Act, which mandates the disclosure of crime statistics and security information on college campuses, a hate crime is “a criminal offense that manifests evidence that the victim was intentionally selected because of the perpetrator’s bias against the victim.” Reportable categories of bias are limited to race, gender, religion, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and disability.

Miller said that everyone involved in making the decision has attended trainings and national conferences on how to evaluate hate crimes.

Miller would not disclose the people involved. He said that some staff are retired law enforcement officers and do not prefer to have their information made public.

“We recognized long ago that the campus recognizes us collectively and that the actions of one staff member can either raise up, or damage the entire department,” he said. “When there is a question or concern, I feel that it should suffice that we only identify a “working group” inside of our department.”

Campus demands transparency

While the College acted legally, many students and faculty questioned its reporting process and transparency, and felt that the campus deserved to know about the incident as soon as it was discovered.

“The KKK is a terrorist organization that targets blacks, Jews, socialists, labor organizers, and LGBT people. If there is reason to suspect that someone on this campus supports their agenda, I want to know about it,” said Nichter.

Papaa Kodzi (‘20), a student in Nichter’s class, sent a message to a group chat of students from Rollins’ Black Student Union (BSU) notifying them of the incident. “I don’t think Campus Safety knew how many students had already seen it,” said Kodzi, regarding the reaction of Rollins to the lack of timely notification immediately following the incident.

“Rollins has a responsibility and an obligation to tell us the whole truth. They don’t get to decide what information to shelter us from,” said Kodzi.

An email notifying the campus about the vandalism was eventually sent over a week later, on Wednesday, March 27, by Abby Hollern, director of the Center for Inclusion and Campus Involvement, the office that oversees student organizations and supports diverse learning experiences for students.

Hollern explained in the email that the incident did not qualify as a hate crime under the Clery Act and included a statement from President Grant Cornwell.

“While this does not technically qualify as a hate crime, it is certainly hateful and would be perceived as threatening to many whom are most vigorously and affirmingly welcome in our community,” said Cornwell in the email. “It seems as though the current political climate has given license to more, more public, and more unashamed expressions of hate, prejudice, and bias, but I trust you stand with me in saying, not at Rollins College.”

Hollern said that, to her knowledge, “there have been no similar incidents that are on the verge of a hate crime but didn’t classify.”

However, students felt the email came too late. The BSU organized a Tars Talk, a recurring event designed to help facilitate conversation between the campus and administration, to discuss the incident and its impact on the minority community. Kodzi and Hollern said the administration’s initial reason for not wanting to send out a Timely Notification was fear of inciting copycat incidents on campus.

There was some debate over whether only students in BSU or only minority students should receive the email, which caused backlash from students and faculty.

Members of the BSU raised concerns about whether the college should be having a larger conversation regarding racism if the fear of copycats is prevalent enough to sway administration to not make information public.

“If we are going to denounce this type of behavior, we need to send this message to all of campus, not just minority students. It applies to everyone,” said Kodzi.

Hate crimes on the rise

Across all Rollins programs, African American students make up only 5.4 percent of the student population, which is roughly 170 students of the 3,127 students when considering all undergraduate and graduate programs. White students make up 55 percent of the overall campus population.

“When I’m within the black community, I feel at home, like I’m part of a big family,” said Kodzi. “It can be a little isolating… being a minority student on campus.”

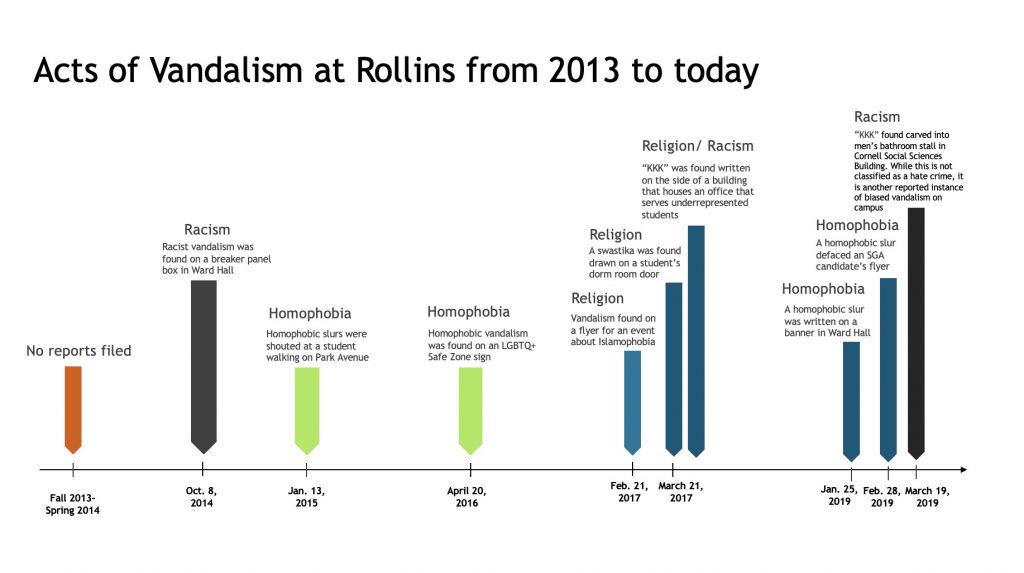

While being a minority student comes with its obstacles socially, it also comes with physical and social threats, which have increased at Rollins in the past few years. Within five weeks in 2017, three hate crimes were reported.

The first act, which was Islamophobic, occurred on Feb. 21. One month later, on March 21, a swastika was drawn on a student’s door. One week after that, on March 28, the letters “KKK” were found written on the side of the Rosen Building, which houses Upward Bound, an organization providing opportunities for minority high school students.

This semester has seen three biased acts of vandalism thus far, two which have been deemed hate crimes under the Clery Act. On Jan. 25, a homophobic slur was found written on a banner in Ward Hall. Approximately one month later, on Feb. 28, another homophobic slur was found on a flyer for an SGA candidate.

This increase is consistent with the national hate crime statistics as reported by the FBI, which reported a 17 percentage point increase in hate crimes from 2016 to 2017. On American college campuses, this number was a 25 percentage point increase, according to the U.S. Department of Education. A majority of these hate crimes, mostly vandalism and destruction of property, were committed against multiracial victims, African Americans, and Jewish people.

Across American college campuses, there was an increase in white supremacist propaganda by 77 percentage points in the 2017-2018 year.

The vandalism was painted over, but the impact of it remains. For students like Kodzi, it was a wake-up call to the country’s political climate. “Racism isn’t dead in America,” he said.

What should be done?

In its mission statement, Rollins outlines a vision of a “healthy, responsive, and inclusive environment” for a liberal arts education. While Rollins responded to this situation with small steps in accordance with its mission, members of the campus community feel there are stronger, more overt tactics that can be used to combat these instances of hate in the Rollins community and beyond.

Students at the Tars Talk on Thursday came up with a rough list of possible solutions, including an expansion of the non-discrimination policy, orientation programs akin to those orchestrated by the Title IX office on campus, visible repercussions for perpetrators of hate crimes and bias incidents, and increasing awareness of the Bias Incident Response Team. This is a team of several faculty and staff who are trained to support victims and refer them to resources, as well as educate the campus about bias’ negative impact.

More effective tactics for hate-related incident prevention and response could look like the mandatory racial-sensitivity training that is required for incoming students or increased safe spaces for minorities on campus.

Be First to Comment