“In the backwash of Fennario

The black and bloody mire

The dire wolf collects his due

While the boys sing ‘round the fire”

– Grateful Dead, “Dire Wolf”

In the same month Donald Trump moved to block states from enforcing climate change policies—the very crisis threatening eight percent of all living animal species—Colossal Biosciences claims to have brought back the dire wolf, the largest of the Late Pleistocene canids, last seen 10,000 years ago.

On April 7, 2025, headlines from major media outlets, including ABC News, Time, USA Today, and CNN, broke the same story: the resurrection of the dire wolf. Colossal Biosciences, a bioscience and genetic engineering company, had brought it back. Colossal is self-described as “the advanced genetics and biosciences company that’s developing the science that will save us, our planet, and the species that inhabit it.”

But don’t get confused—“We’re not a foundation, we’re not a nonprofit, we are not an academic think tank. We are trying to actually develop products and build technologies,” said Ben Lamm, the company’s CEO and co-founder, in an interview with ABC News.

Meet: The Dire Wolf

The dire wolf once prowled the vast terrain of North America, ranging from the icy reaches of Alaska to the arid deserts of Mexico. Fossils of the dire wolf have been found on both coasts of the United States, as well as central, southern, and southwestern regions. The range in the dire wolf distribution indicates that it was adapted to a variety of habitats, ranging from tropical wetlands to boreal grasslands. These canids shared the landscape with other Pleistocene megafauna, including woolly mammoths, camels, giant ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats. Welcome to the Pleistocene epoch—a geological era that spanned from about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago. Marked by repeated glacial and interglacial cycles, the Pleistocene was a time of dramatic climate fluctuations.

Dire wolves were menacing hunters. The prehistoric dire wolf once co-existed with the gray wolf—the species of wolf we still have today. Weighing anywhere from 125 to 175 pounds, the dire wolf is estimated to have been about 25 percent heavier than the modern gray wolf. The gray wolf shares morphological characteristics with the dire wolf, including head and body shape; this resemblance once suggested the two species shared an evolutionary ancestor. However, more recent genetic data suggest that the dire wolf may be more closely related to the modern-day jackal, placing it in an entirely separate genus.

Dire wolves were carnivorous, with isotopic analysis suggesting their diet focused heavily on horses; ground sloths, camels, and bison made up less of their intake. Many dire wolf fossils found together at Rancho La Brea indicate that these wolves were also social animals, forming communities to hunt and raise offspring.

Dire wolves roamed the Americas for at least 250,000 years; however, the fate of this species is still widely speculated. While they became extinct near the end of the last ice age, the reasoning behind their disappearance remains a topic of debate. Some researchers point to rising temperatures and climate change, while others speculate the evolution of humans—or even a giant comet—as contributing factors to their absence from today’s megafauna.

A Colossal Problem

“On October 1, 2024, for the first time in human history, Colossal successfully restored a once-eradicated species through the science of de-extinction,” reads Colossal Biosciences’ website. Two dire wolf pups, Romulus and Remus, were born last fall in October, but their two-month-old sister, Khaleesi, wasn’t introduced until this past winter. The pups had been “chasing, nipping, nuzzling, and tussling” over the course of the year—but it wasn’t until April 2025 that their existence was made public.

Using DNA extracted from a fossilized tooth and skull, scientists sequenced the genome of the dire wolf and compared it to that of the gray wolf. After identifying 20 key genetic differences across 14 genomes, researchers edited gray wolf DNA to express characteristics typical of the prehistoric dire wolf, such as larger body size and more robust teeth. The edited nuclei were then extracted from these modified cells and inserted into gray wolf ova from which the original nuclei had been removed. These ova developed into embryos, which were implanted into the wombs of two domestic hound breeds, and after 65 days, Romulus and Remus were born.

However, calling this the “de-extinction” of the dire wolf is not entirely accurate. While dire wolves and modern gray wolves look similar, this is the result of convergent evolution, where unrelated species can develop similar traits due to similar environments or adaptive pressures. A DNA study published in 2021 found that dire wolves belonged to a much older evolutionary lineage of dog.

“Dire wolves, it now appeared, had evolved in the Americas and had no close kinship with the gray wolves from Eurasia; the last time gray wolves and dire wolves shared a common ancestor was about 5.7 million years ago,” said an article published by Scientific American in 2021.

Dire wolves emerged from a lineage more closely related to African Jackals rather than the Gray Wolf.

Colossal acknowledges this in their preliminary pre-print paper, published April 11 of this year. “Although Perri et al. confirmed that dire wolves are a distinct evolutionary lineage, a high frequency of phylogenetic incongruence among estimated gene trees led to uncertainties about their early evolutionary history.”

The biogenetics company proposes the possibility of an early species of canid interbreeding with jackals and wolves.

Melanie Challenger, the deputy co-chair of the Nuffield Council on Bioethics in the United Kingdom, said in an interview with CNN Science, “It’s not de-extinction, it’s genetically engineering a novel organism to fulfill the functions, theoretically, of an extant (living) organism. You’re not bringing anything back from the dead. And all the way through the process, there are different, quite gnarly ethical considerations.”

The ethics of “de-extinction”

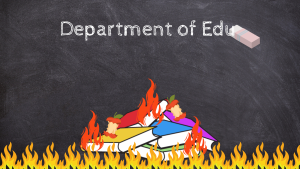

De-extinction is not a resurrection of species that no longer exist. The dire wolf, like the woolly mammoth, the dodo, and the great auk, is a creature humanity will never fully witness again.

Beth Shapiro, Colossal’s chief science officer, told CNN: “We aren’t trying to bring something back that’s 100 percent genetically identical to another species. Our goal with de-extinction is to create functional copies of these extinct species. We focus on identifying variants that will produce key traits.”

But what purpose does it serve to recreate an animal if we no longer have the vast habitats they once roamed, the prey they depended on, or the ecosystems they helped shape?

De-extinction often overlooks the very reasons species disappeared in the first place: habitat fragmentation, rising global temperatures, invasive species, and the complex relationships that defined their existence. Reducing an animal to a set of physical traits isn’t just ethically questionable, it also ignores the intricate systems those creatures were a part of.

The only way to “bring back” a species is to ensure they never vanish to begin with.

The opinions on this page do not necessarily reflect those of The Sandspur or Rollins College. Have any additional tips or opinions? Send us your response. We want to hear your voice.

Comments are closed.