“When you need medical service, you bring doctors and nurses. When you need the rebuilding of infrastructure, you bring in engineers and architects. And if you have to feed people, you need professional chefs.” –José Andrés

Just under 23 miles from Rollins, you’ll find one of the United States’ first prosperous tapas restaurants. Perhaps you’ve heard of Jaleo, the upscale Spanish restaurant with locations ranging from Dubai to Disney Springs, Chicago to Las Vegas, and finally to its first location in Washington D.C. The creative mastermind behind it all?

Chef José Andrés.

The celebrity chef, who just received a Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Biden on January 4, has pioneered a new form of emergency relief that is saving lives in Ukraine, Gaza, and now Los Angeles.

It’s safe to say Andrés has defied the typical patterns of celebrity chefs. While TV-friendly personalities like Gordon Ramsay, Rachael Ray, Bobby Flay, and Guy Fieri have risen to fame through television deals, branded products, flashy cookbooks, and restaurants baring their names in bold, José Andrés received acclaim through his quiet commitment to cultivating a culinary craft built on his heritage, coupled with a passion for humanitarian relief and education. The PBS specials and retail products were merely a byproduct of restaurants like Zaytinya, Oyamel, and minibar winning over the public’s taste buds.

Over the years, he has taught courses at George Washington University’s Sustainability program, examining the food industry and food-related health issues as well as immigration and the undocumented food system.

As an immigrant turned naturalized citizen himself, immigration advocacy is a monumental part of Andrés’ mission, as he shared on a Tufts University podcast:

“Sometimes being American or belonging to a country is not by the passport you own, but by the heart you put in the everyday in your community. That’s what makes a person belong to a place. And those people, they are ghosts in our own community. Our senators and congressmen today are being fed on the shoulders of eleven million undocumented, underpaid, sometimes mistreated, et cetera, et cetera. We have to put an end to that injustice. So I just see food as immigration reform.”

The José Andrés Group runs 31 successful restaurants, including a 2-Michelin star restaurant and a food truck, with cuisine inspired by Spain, Central America, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and more. But his greatest impact arguably lies in World Central Kitchen (WCK), a nonprofit, non-governmental organization leading food relief efforts by providing fresh meals in the wake of humanitarian, community, and climate crises around the globe.

World Central Kitchen

José Andrés founded WCK in 2010 following a catastrophic earthquake in Haiti that killed 300,000 and displaced over a million Haitians. Instead of turning to Twitter or a conciliatory statement, Andrés traveled to Haiti and got to work.

Haitians living in a relief camp taught him how to prepare traditional beans and dishes; the NGO’s entire mission is founded on this belief that comforting people in times of disaster is best achieved by hiring locals to prepare dishes specific to the region.

He helped train cooks and build schools in Haiti, but this was merely the beginning. Andrés put this philosophy into practice, serving thousands in Houston after Hurricane Harvey in 2017, and then in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria, decked out in his signature “Orvis fly-fishing vest like a battle jacket with rolls of cash in one pocket and cigars in the other,” as the NYT reported.

Puerto Rico, 2017

Leadership and change need not always come from the political level, as was proved when the 2017 presidential administration withheld $20 billion in relief funds for Puerto Rico after the deadly hurricane killed 4,645 citizens.

World Central Kitchen, on the other hand, went to Puerto Rico immediately following the 16-hour ravaging of the island, where it proceeded to prepare nearly 4 million meals with the help of twenty thousand local volunteers. Andrés worked with the Red Cross, FEMA, and Salvation Army to provide aid—distributing food as a means of getting intelligence on what people needed and where they needed it instead of cooping up with the government workers in a convention center.

Still, WCK learned its responses needed to be faster.

North Carolina, 2018

The WCK team stationed themselves in Raleigh and Wilmington four days before Hurricane Florence hit. The kitchens were functioning and feeding first responders before. In doing so, they turned traditions of relief efforts around completely, which tend to propose spending millions on self-contained meals or MREs after disaster strikes and bringing all materials and people from the outside. WCK was set up in five local kitchens with refrigerated food trucks, generators, and gas, using local distributors and chefs.

Ukraine, 2022-present

It has been nearly three years since Russian forces launched their large-scale invasion of Ukraine, and World Central Kitchen has been stationed in Ukraine since just after the initial attack:

“Our Ukrainian-led teams have brought much more than meals to neighbors in need. Each day we stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the Food Fighters of Ukraine to provide hope and a sense of home, one meal at a time.”

They have served over 260 million meals to Ukrainians in dire need with their #ChefsForUkraine movement.

To hear real stories of their experiences on the ground, you can register to tune into WCK’s virtual event on February 28.

Gaza, 2023-present

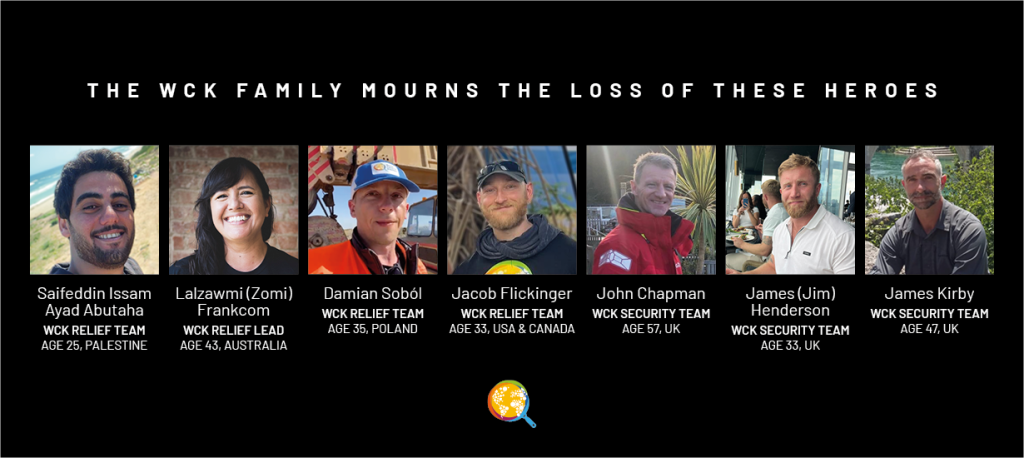

In April of 2024, an Israeli airstrike killed seven civilians on a World Central Kitchen mission to feed Palestinians—workers who courageously entered the grounds of a conflict that has now seen over 46,000 Palestinians killed by the Israeli military. The NGO released a statement clarifying the workers were in a deconflicted zone in armored cars branded with the WCK logo and that they had coordinated their movements with the IDF. However, they got hit just after unloading over 100 tons of humanitarian food aid delivered through a sea corridor.

WCK’s CEO, Erin Gore, said at the time, “This is not only an attack against WCK, this is an attack on humanitarian organizations showing up in the most dire of situations where food is being used as a weapon of war. This is unforgivable.”

In addition to providing hot and nutritious meals and food supplies to Israeli seniors and disabled people unable to leave the country, while delivering meals to hospitals as Israeli hostages returned, WCK has distributed nearly 90 million meals in Gaza, earning two Gold Anthem Awards.

They set up their first-ever mobile bakery in Gaza in January of 2025, which can make up to 3,000 pitas an hour to accompany the “nourishing plates of food” prepared by their local chefs.

Los Angeles, 2025-present

As of Jan. 28, 2025, WCK is operating out of 21 locations in Southern California to help feed those displaced or experiencing hardships amidst multiple wildfires that erupted at the start of the month. The fires, which have killed 29 people, are finally nearing full containment with the help of weekend rainfall.

It’s not just people in danger, either. One man, Sergio Marcial, helped rescue over 70 animals from the Eaton Dam Stables, ending up in the hospital with his lungs and throat burning after his face mask caught on fire from the intensity of the flames.

It is often the case that WCK gets on the ground even faster than FEMA, within the first 24 or 48 hours of a crisis. WCK Chef Corps member Tyler Florence is working on the edges of the fires to help give first responders warm meals. He told Food & Wine,

“This is what we do. We open up our restaurants every night with a sense of welcome. We know how to produce high-quality food at scale and how to organize and run teams. It’s also what we do from an entertainment standpoint. If you come into our restaurants, it feels like a good time, but on a base level, we know how to feed people and that is vital in emergency situations.”

Southwest Florida, 2022

After Hurricane Ian ravaged my hometown of Sanibel Island, as well as nearby areas of Fort Myers Beach and Pine Island, World Central Kitchen was there to do what they do best: provide comfort and critical support through serving as many as 200,000 meals just one week after the catastrophe. The team had set up in Tampa, but it soon relocated to Fort Myers, as WCK shared:

“We landed on Sanibel Island the first day it was safe to fly and brought sandwiches to rescue teams to take to families who had stayed on the island. Following that, Chef José took fresh meals to residents on Pine Island, and we’ve returned to both locations every day since.”

See this video of Chef José Andrés on the ground in Pine Island just after Ian hit.

“The Best of Humanity”

A meal provides both emotional and physical needs—WCK knows this very well. José Andrés wrote an op-ed to The New York Times entitled “Let People Eat” that encapsulates the importance of sharing food and preserving the safety of those who dare to help the less fortunate. Not long after the WCK workers were killed, he shared,

“The seven people killed on a World Central Kitchen mission in Gaza on Monday were the best of humanity. They are not faceless or nameless. They are not generic aid workers or collateral damage in war … Their work was based on the simple belief that food is a universal human right. It is not conditional on being good or bad, rich or poor, left or right. We do not ask what religion you belong to. We just ask how many meals you need.”

“It is not a sign of weakness to feed strangers; it is a sign of strength. The people of Israel need to remember, at this darkest hour, what strength truly looks like.”

As American aid programs that alleviate malnutrition, provide clean water, medicine, and countless other critical services around the world are at risk of being shut down due to the current U.S. administration’s executive order to halt foreign aid, let us all remember what real strength looks like. It lies in helping those who are less fortunate and defending universal human rights to food and health. It lies in our capacity for humanity toward those who need it the most.

The opinions on this page do not necessarily reflect those of The Sandspur or Rollins College. Have any additional tips or opinions? Send us your response. We want to hear your voice.

Comments are closed.