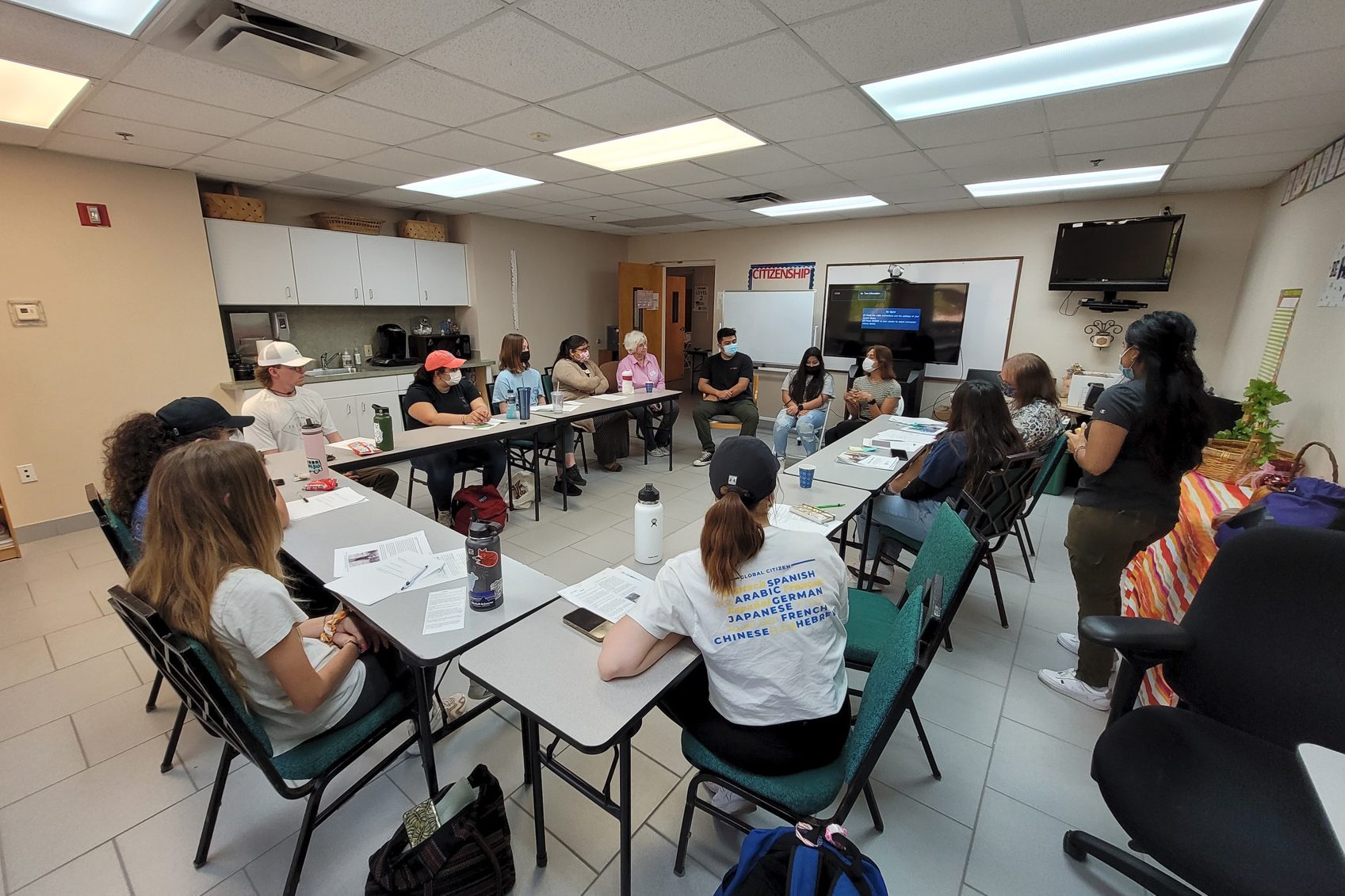

We took a trip with our “Environment, Migration, and Society in Latin America” course to get to know both migrant and seasonal farmworkers living in Apopka, Fla. and its surrounding areas last month. At the height of Women’s History month, we were left wondering about the difficulties women who work within this community face and the burdens placed on them due to their intersectional identities.

While on this class trip, as well as through interviews, we were able to get a better understanding of the many roles and responsibilities of farmworkers, as well as the overlap and additional struggles women face within the field.

One of our interviewees was Yesica Ramirez. Ramirez is the Area Coordinator and Community Organizer for the Farmworker Association of Florida (FWAF) and has worked with the organization for 10 years as of March.

During our interview, Ramirez explained that she is the mother of three children. During one of her pregnancies, Ramirez discovered that the pesticides used in the plant nursery she was working in negatively affected her third child’s health. She said, “…[D]uring all the training I took at the Farmer’s Association of Florida, there was a possibility that the chemicals I used on the plants could affect the health of my baby and myself. I tried to take care of myself during my pregnancy, but the nursery did not offer me the proper protective equipment.”

One month after Ramirez gave birth, doctors found that her baby suffered from Craniosynostosis, a congenital disability where the bones in a baby’s skull join together too early. Ramirez’s four-month-old baby underwent surgery, and a helmet was placed around the child’s head for months after.

Ramirez explained that many farmworker mothers have a limited number of days to take off if one of their children gets sick. She said, “…A lot of the time you can’t control that your kid won’t get sick, or not having someone to watch over your kids, because that’s another issue if you don’t have anyone to watch over them.”

Ramirez emphasized how mothers don’t and can’t afford to miss work. The income received is the reason why they endure burdens in the nurseries. Ramirez said that, during her time in the nursery, she “only made $7.25, so the issues of income and living day by day and then having to lose money is complicated.” Being a working mother in her field is problematic because women are responsible for maintaining a healthy family as well as maintaining their own health while working in the field.

Another very important, yet sometimes overlooked problem for women farmworkers is the abuse and harassment that these women endure. During our interview, Ramirez elaborated on a few cases that she came across in which women were harassed and forced to take part in sexual activities with their supervisor due to power imbalances. Women experience harassment from their coworkers as well.

Some misogynistic men take advantage of their position in power, and women pay the consequences. Many outsiders ask, why don’t these women leave? But as Ramirez said, the environment these women are surrounded by makes them more vulnerable and submissive, and it is harder for them to speak up.

If these women do speak up, they may be threatened with deportation; being fired, which would mean a loss of income on which their families are dependent; or being publicly exposed with videos and photographs. Ultimately, the women have no alternative but to continue doing what they are doing.

Bringing awareness to these labor abuses is just the first step in helping women farmworkers and their families, which is what FWAF strives to do, and much more.

Many farmworkers face challenges when it comes to obtaining H-2A visas. An H-2A visa is a program agricultural employers use to bring foreign workers to perform temporary agricultural labor. Ramirez said, “In Florida, most H-2A workers are men and for various reasons. One is because they are ‘the stronger workforce.’” Another reason is that it is easier not to look for and provide separate housing for women and men in a hotel or other form of worker housing.

Employers and companies often manipulate migrant workers. Within the H-2A program, employers and companies violate worker contracts, underpay workers, and do not provide adequate housing. Additionally, Many H-2A workers risk and face human trafficking because employers take advantage of them.

“We have come across cases where these workers are paid only $70 or $80 a week, despite working 8-hour shifts a day,” Ramirez said. “Sometimes they are not given adequate housing; their employer will put ten men in one tiny room stacked upon each other.”

Despite the distinct challenges that women face within the field, they still face similar challenges to male farm workers, as they must put their health at risk in the workplace. Ramirez faced health risks both in relation to pesticides while doing fieldwork and in a previous office job placement. While she was pregnant with her third child, she described facing conditions where “…we still mixed Clorox/bleach with alcohol to clean the tables all day….” When mixed, these substances create chloroform, a danger she didn’t face before.

Acknowledging these challenges is the first step in a long process of changing the narrative that we see around migrant workers. Other ways we can support this community-based, grassroots group of people is by supporting organizations like the FWAF, which directly works toward changing laws and advocating for farmworkers in Florida.

The opinions on this page do not necessarily reflect those of The Sandspur or Rollins College.

Have a differing or additional opinion? Send us your response. We want to hear your voice.

Comments are closed.