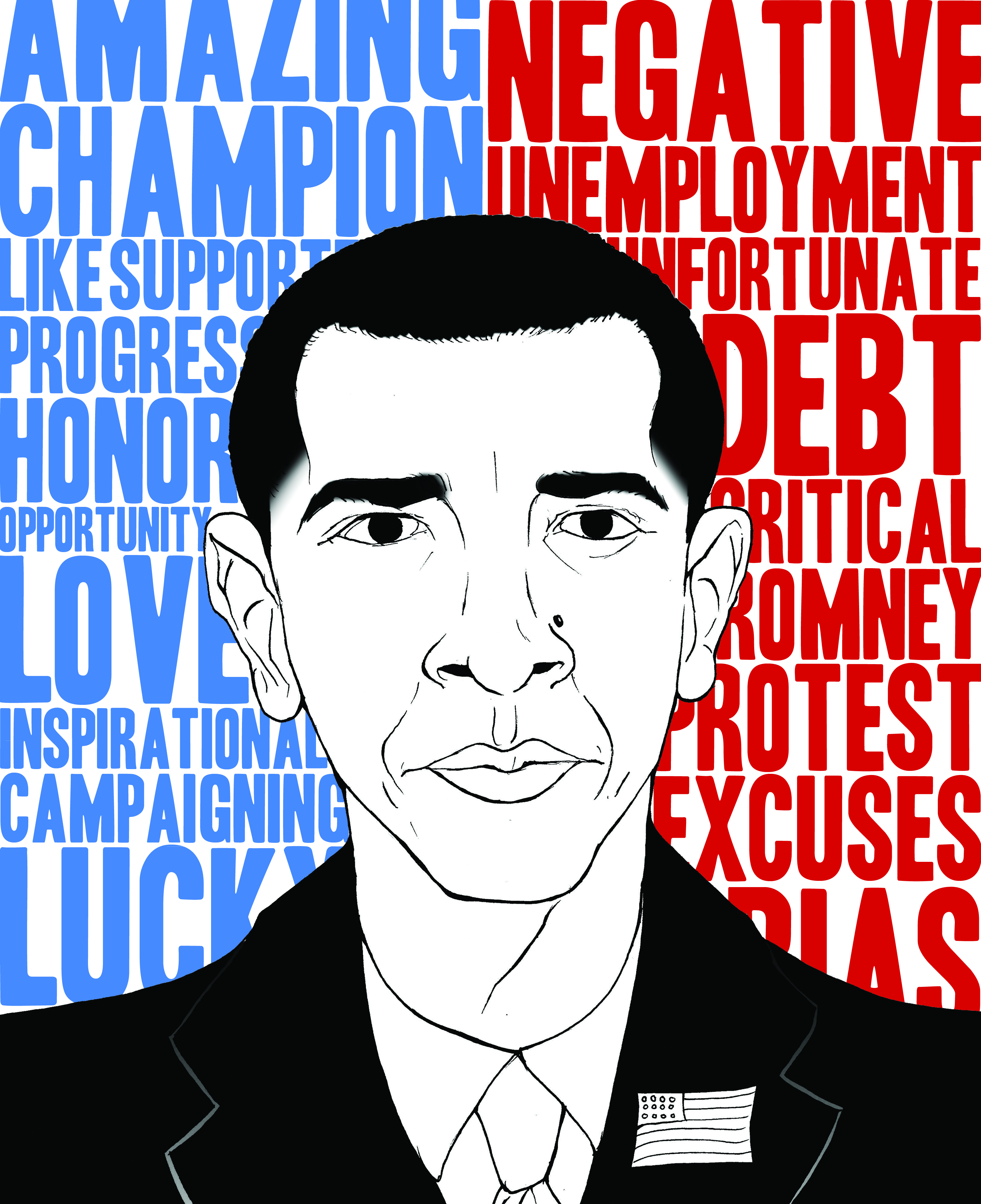

August 2, 2012: It would have been a hot, still summer afternoon like any other at Rollins, if not for the protestors. They were gathered in front of the SunTrust Plaza parking garage, across the street from a gutted Bush Hall, waving signs. On some signs were written slogans supportive of Republican nominee Mitt Romney. On some were written slogans critical of incumbent Barack Obama—on more. Among the protestors was Dan Berlinger ’13, chair of the College Republicans of Rollins College—“to give Republicans a voice,” he said. He was there, presumably, because Democrats already had a voice on campus that day: President Obama was due to speak in the Alfond Sports Center a little before 3:00 p.m.

August 2, 2012: It would have been a hot, still summer afternoon like any other at Rollins, if not for the protestors. They were gathered in front of the SunTrust Plaza parking garage, across the street from a gutted Bush Hall, waving signs. On some signs were written slogans supportive of Republican nominee Mitt Romney. On some were written slogans critical of incumbent Barack Obama—on more. Among the protestors was Dan Berlinger ’13, chair of the College Republicans of Rollins College—“to give Republicans a voice,” he said. He was there, presumably, because Democrats already had a voice on campus that day: President Obama was due to speak in the Alfond Sports Center a little before 3:00 p.m.

August 2, 2012: Protestors and President aside, just a normal afternoon at Rollins College.

Hours earlier—around 6:30 a.m.—spectators started lining up outside Alfond. Soon, the line had spilled onto the sidewalks lining Fairbanks Avenue and, by midmorning, it had reached the school’s main entrance at the intersection with Park Ave. And if nine hours—nine hours in stultifying, Florida-in-August heat, the only reprieve from which were intermittent, Florida-in-all months downpours—seems like a long time to wait for a 30 minute address, that’s because it is. But many people standing in line to see the President speak had been waiting a lot longer than nine hours. They’d been waiting two weeks.

Obama was originally scheduled to speak at Rollins two weeks earlier, on July 20th—the same day James Holmes, during a midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises at a theater in Aurora, CO, killed twelve moviegoers and injured nearly 60 more. The President, who’d been campaigning in Florida, postponed his speaking engagement and returned to the White House, to lead the nation in mourning. It would be fourteen days until ticketholders could put their tickets to use.

Many in the community were glad to be afforded another opportunity to see the President speak. Others were less pleased.

Many in the community were glad to be afforded another opportunity to see the President speak. Others were less pleased. On Rollins’ Facebook page, a link announcing Obama’s decision to reschedule his speech was met with several negative comments, the most striking of which read, “I really had hoped we dodged this bullet,”—a grim pun made in light of the shootings in Aurora. Barack Obama was every bit as polarizing at Rollins as he was everywhere else in the country.

On the afternoon of the 2nd, the sun was omnipresent—was obstinate in its refusal to cut the assembled crowds a break. And Steve and Holly Gauthier were undiscouraged: They had been waiting several hours to see the president and, despite the punishing elements, they were excited. “We like Obama,” Ms. Gauthier said. “We’d love to hear him speak.” Meanwhile, across the street, Dan Berlinger and the other Rollins College Republicans were joined by Tea Party delegations from both east and west Orlando, and a group of UCF College Republicans. While the Gauthiers and a few thousand others filed into the Alfond Sports Center, the Secret Service restricted protestors to the parking garage.

Just before 3:00 p.m., Barack Obama ascended the steps leading to a lectern custom-built a day earlier. The President was ecstatically received, eliciting the same cheer—“O-BA-MA!”— he has since his keynote speech at the 2004 Democratic National Convention. In his speech, the President vowed to fight for the working class, expressed serious doubt Mitt Romney cared much about doing the same, and asked God to bless the country and everyone in it. The address was a textbook stump speech, simultaneously rousing and anodyne—exactly like a Romney stump speech in tone, and similar in content. But given to a slightly different end.

The address was a textbook stump speech, simultaneously rousing and anodyne—exactly like a Romney stump speech in tone, and similar in content. But given to a slightly different end.

“Inspirational as usual,” said Derrick Boisette ’15, a member of a Democratic organization on-campus. Given Boisette’s activism for President Obama’s party, it would have sounded like a peculiarly ambivalent verdict, but it seemed to be shared by all in attendance. In his remarks following Obama’s address, Rollins College President Lewis Duncan said, mildly, “It’s very nice for Rollins to share in the democratic process.” And it is.

The opposition was bitter and intransigent, the supporters were filled with breathless enthusiasm, and the speech itself was—decent. Pretty OK. Eloquent or whatever. If the President’s visit was any indication, political participation means desperately wishing being passionate about something can make that thing worthy of your passion. And, like Dr. Duncan said: It’s nice, that wish.

Be First to Comment