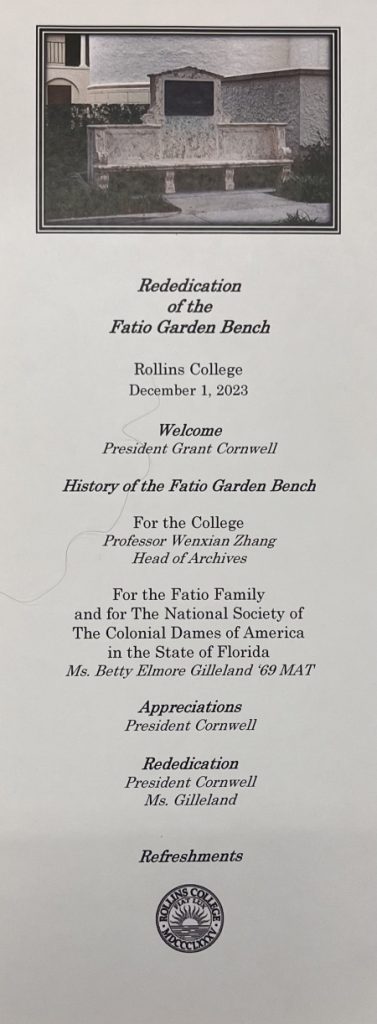

A weathered coquina bench lies in Rollins College’s Chapel Garden; the cracks in its restored frame tell the fragments of two stories: one of early environmental preservation, another of enslavement.

Restored and rededicated in December 2023, the Francis Philip Fatio memorial bench has brought to light an enduring conversation about how educational institutions should address complex historical legacies.

The complicated history of this bench was uncovered by former history student Liam King (‘24).

“I am working on a project called Locating Slavery’s Legacies,” said Claire Strom,

professor of history at Rollins College. “And what we’re doing is locating

memorials to people who had some perspective on racial matters—enslavers, abolitionists, white supremacists, civil rights activists—on the Rollins College campus.”

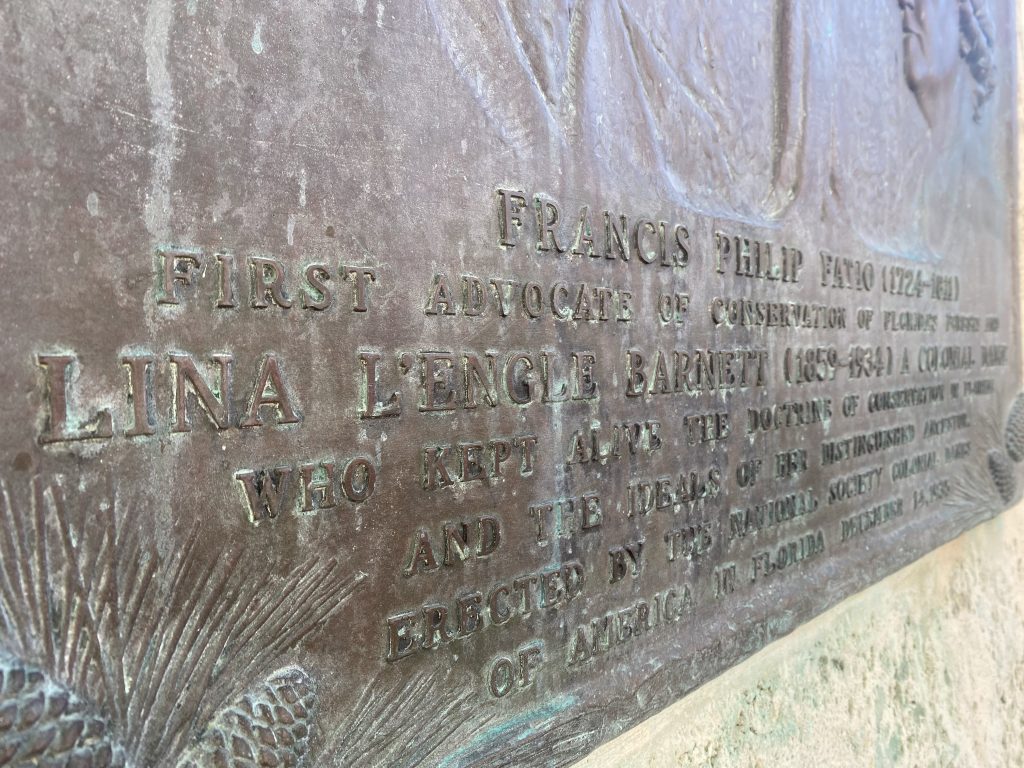

This project was one that King worked on in her final semester at Rollins in the Spring of 2024. Pouring through any named memorial on the campus, King discovered the Francis Philip Fatio and Lina L’Engle Barnett memorial bench.

Francis Philip Fatio was born in Switzerland in 1724 and would not make his way to East Florida until 1771. Fatio then went on to acquire a 10,000-acre land grant in St. Augustine which he named New Switzerland. On this land, he would soon become one of the wealthiest men in East Florida in the 1780s. His riches, however, were slave-harvested.

By 1787, Fatio had 82 enslaved people, which encompassed nearly a third of all enslaved people on the St. Johns River at that time.

With the wealth Fatio earned through his plantation, he funded his scientific pursuits. He had a particular fascination with trees and in many ways used his wealth to become one of the first early advocates of conservation.

“So Fatio is being honored because he was an early environmentalist. And that’s

completely true,” said Strom. “The fact that he was looking at preserving Florida’s

environment, so that he could make tons of money from it with his slaves is also true.

These two facts can co-exist.”

Strom raises the question which permeates much of higher education in addressing these complex legacies: “The question I come back to is, do we feel okay honoring someone who did something we find abhorrent if they also did something valuable? And I don’t know the answer to that,” she said.

This is not the first time that Rollins has had memorials on campus dedicated to people who supported slavery.

In 2020, President Grant Cornwell sent out an email to the campus addressing the college’s racial justice initiatives in response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Among the initiatives to incorporate racial justice more into the curriculum and creating student learning groups, he addressed a “specific and humble gesture signaling that Black Lives Matter in the Rollins College campus community.”

President Cornwell removed 9 stones from the Walk of Fame, the hundreds of stones that encircle Mills Lawn, that represented advocates of slavery and Confederate officers. He considered that “reckoning with history, our nation’s and our own, is an essential dimension of racial justice.”

President Cornwell does note that “there may be other stones commemorating persons who would not stand up to critical scrutiny were we to use our mission as a lens.” His gesture at the time was one to act “as a symbol of both protest and reconciliation.”

“The thing about that is that there are many other stones in the Walk of Fame that are problematic,” said Strom. “A guy called Albert Pike is still in the Walk of Fame, and he was a Confederate general and owned slaves. But who’s heard of Albert Pike? Who’s heard of Fatio? We’ll get rid of Robert E. Lee because everyone knows him.”

Three years after the removal of these stones, President Cornwell would go on to remove the Fatio bench from storage and rededicate it on December 1, 2023.

The bench holds a complex timeline on Rollins’ campus. It was donated in 1935 by the National Society of Colonial Dames, which L’Engle Barnett was an active member of. The bench was then taken down during construction in 1980 and was eventually disassembled and sat lost in storage for many years.

When Betty Gilleland, descendant of Fatio and friend of former Rollins president Rita Bornstein, requested the bench’s reinstalment, it was soon found and restored and placed where it sits in the Chapel Garden today.

During the speech, Gilleland addressed the plantation owned by Fatio but never mentioned the enslaved people, rather focusing on Fatio and L’Engle Barnett’s leading work for environmentalism.

Strom does not see any one right way to address the layered history that surrounds this memorial.

“You can find flaws in everybody, but you should at least acknowledge them, I think,”

said Strom.

It is this acknowledgement of history that King worked toward in uncovering the complexities of the people who are memorialized or idolized.

“Despite some apprehension, we are unswervingly proud of King and her urgency to reckon with the past,” said Strom in a blog. “Her story shows the power of history, research, and archives to move institutions in the right direction. We need to encourage and empower our students to share the fruits of their research widely and openly without worrying about what it will mean for the college’s reputation. We need to foster, inform, be at the center of difficult discussions about the legacy of racism in our communities, and bring that into our teaching and collections work.”

As a historian, Strom sees addressing this history more publicly as an important step in continuing to promote the college’s commitment to diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging.

“The most appropriate way to address this is in some form of analysis. Either you take it down, but you explain why, or you leave it up, and you explain why,” said Strom. “There’s some kind of permanent plaque that contextualizes them. You need to have a consistent policy, which we don’t have, and you need to address all the monuments, not just some of them.”

Comments are closed.