(Photo courtesy of Rollins Department of Archives and Special Collections)

Every Saturday in the fall, Rollins students longingly watch as nearby college students dress in spirited colors and tailgate with peers before heading into a rumbling stadium to cheer on their football team.

As depressing as fall without football can feel, it has not always been this way—in fact, Rollins had a state championship-winning team at one point, and even beat the Miami Hurricanes and University of Florida Gators.

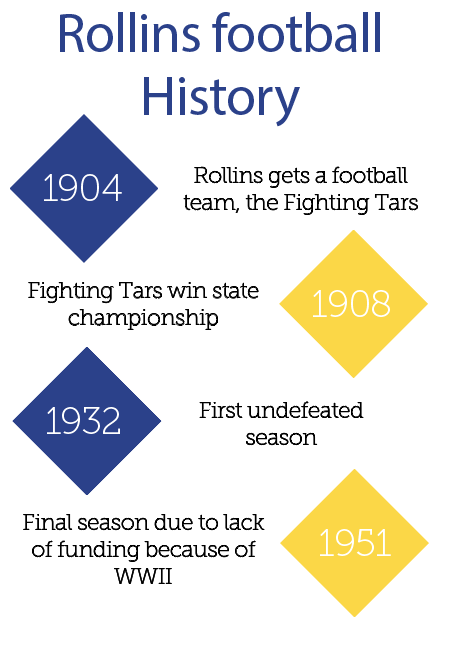

Rollins’ football team, originally called the Fighting Tars, faced adversity since its start in 1904. The game’s brutality worried most parents. That year alone, football was responsible for 18 deaths and 159 serious injuries around the country, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Florida’s sweltering heat worsened this. The fields in Winter Park were full of sandspurs, and the players would go back to the locker rooms aching from all the burrs lodged in their skin and gear. Picking the spurs before practice was even a hazing ritual for the freshmen players.

Considering their first win came in 1906, the Tars caused quite a surprise when they grabbed the State Championship in 1908. On Christmas Day of that year, Rollins became the first American college to play international football when they traveled to Cuba and faced the University of Havana.

Rollins technically inaugurated football in Florida. Talks of a state intercollegiate athletic organization started in October 1914 and concluded in 1917 when Rollins became a founding member of the Florida Collegiate Athletic Association. The Tars led by example in terms of fair play and sportsmanship by consistently fielding more freshmen than their opponents.

The September 1924 Alumni Record said, “Although Rollins inaugurated football in Florida, she has not been able, because of the smallness of the college, to establish an enviable record in scores. But since football has developed into more of a science than a fight, the small college is rapidly assuming its rightful place on the gridiron.”

In 1925, Rollins supported Winter Park’s Rotary Club, an organization based on community service, in organizing a high school tournament. In an attempt to depart from the old traditions, the Fighting Tars changed their name to the Orange Typhoon, only to revert to their original nomenclature the following season.

Hamilton Holt, Rollins president from 1925 to 1949, decided to sacrifice results for the sake of scholarship, demanding recruits who “promise of being good athletes in addition to being good, all-round students and citizens of Rollins.”

The golden era

In 1929, Coach Jack McDowall took charge of the Tars. An All-Southern half-back, McDowall had captained the basketball team and served as first baseman of the varsity team at North Carolina State College. McDowall’s reputation, authority, and understanding of the game set him up for coaching greatness.

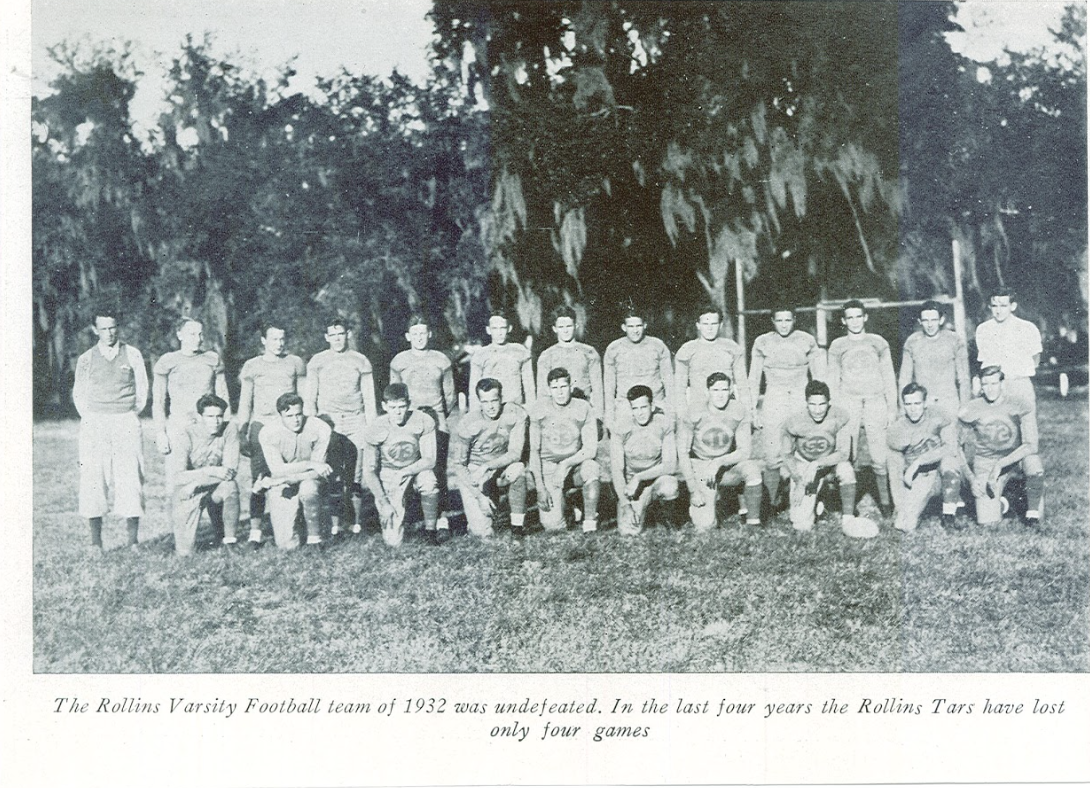

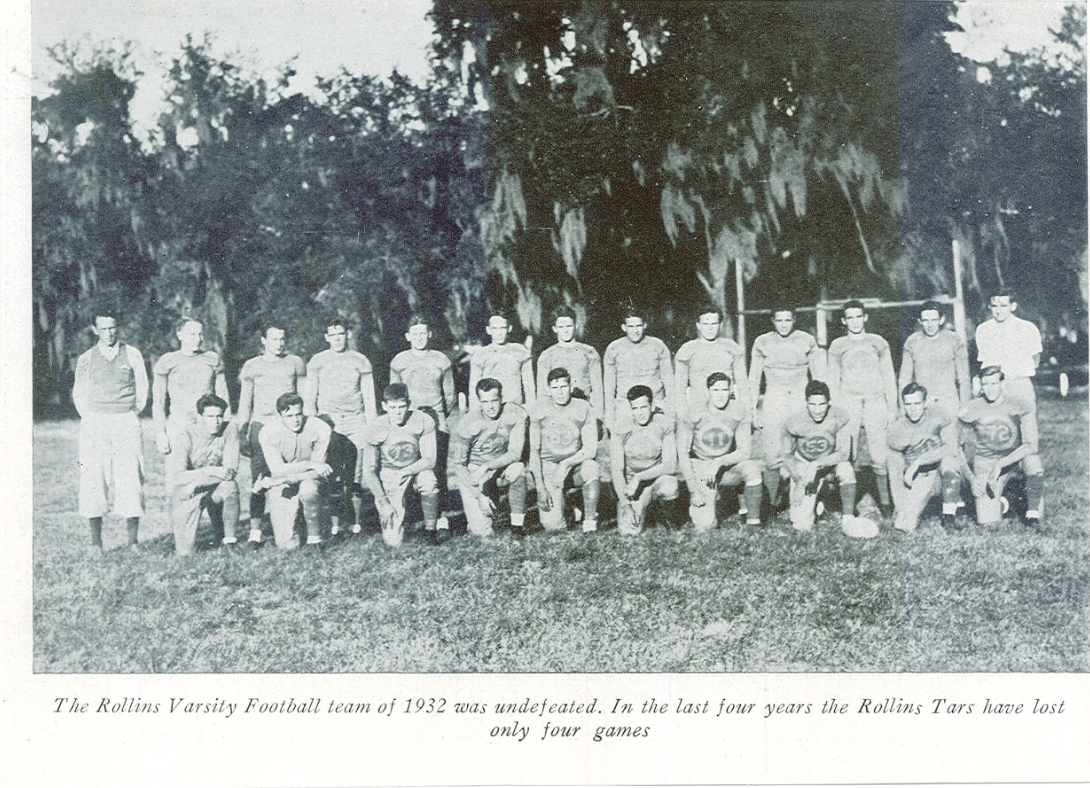

Per the Rollins College News Service, McDowall was “frankly pessimistic” for the 1932 season, as graduation had butchered the backline. “I doubt if we [will] win half our games,” he said. However, that year Rollins went undefeated for the first time in its history, culminating with a 6-0 win against Miami. Phil “Skeeter” Horton, a stand-in quarterback, played the game of his life against the Hurricanes.

Half-back Will Rogers, who had received the Omicron Delta Kappa cup as outstanding athlete of the year in 1931, also had a glorious season. His no. 43 jersey was retired at the end of his Rollins career, only to be worn in the future by outstanding players on the last game of their senior year.

In 1934, Rollins won the unofficial Small College Championship of Florida, beating Tampa in a tense final. The Tars also beat the Florida Gators B team and the Gators refused to play Rollins again until 1948.

World War II reduces funds

Between 1939 and 1940, Rollins played 20 games, winning all but two. However, World War II caused another program hiccup, and this time it never recovered. The G.I. Bill, which provided benefits for returning veterans, incurred huge economic burdens for Rollins, and in 1948 the ticket price to games was lowered in an attempt to attract more fans. Amusingly, the season’s unconventional mascot was a live goat named Witherspoon II.

Yet the main talking point from that season was the homecoming game against Ohio Wesleyan University. An eagerly awaited event, the game had to be cancelled due to controversy surrounding Kenneth Woodward, Ohio Wesleyan’s African-American player.

Despite its liberal convictions, the Rollins administration, fearing potential incidents, considered it dangerous for a player of color to come to, as Holt said, “the deep South.” Holt explained his motives in front of faculty and students, admitting this was not his preferred course of action.

Entering the 1949 season, Rollins was plagued with the departures of key veterans, who were replaced by inexperienced sophomores. Despite having Harry “The Clearwater Bald Man” Hancock, one of the best centers in the South, supported by Joe Swicewood and Buddy High, the team struggled.

However, the real struggle lay in the checkbooks. At this point in time, the program’s costs were double the revenue. Football also used up two-thirds of the sports budget and cost three-and-a-half times more than the new library.

Projections for the 1950-51 season showed that in the best-case scenario, the team could only break even, whereas in the past season it had lost money in three out of four home games. When factoring in the scholarships for veterans and the general economic situation after WWII, it became clear that, despite affection for the game, football had to go.

In 2011, Rollins thought they had found the answer to bring football back. Jeff Hoblick (‘14), a sophomore at the time, made a monumental effort to assemble players, coaches, and enough donations to cover operational costs for a new team—the first one in 62 years.

Although at the club level, it was enough to galvanize the atmosphere on campus. Hoblick served as president and quarterback, and the team played two games the first season, managing a win against Clemson. However, it was a short-lived endeavor. After Hoblick and his cohort graduated, there was not enough manpower to keep the ball rolling. It did show that, despite the lethargy, the spirit of the game had anything but disappeared from Winter Park.

As the former Rollins yearbook, the Tomokan, wrote in 1938: “They were hot and they were cold—those football Tars of ours.” The story of football at Rollins is full of ups and downs, but it is a story of progress, innovation, and, above all, passion—both then and now.

Be First to Comment